By Amanda N. Fisher, Graduate Student, Department of Psychology; Maria K. Anchacles, Undergraduate Student, Department of Psychology; and Dr. Dakesa Piña, Staff Counselor, Student Counseling Services

It is no secret that our culture places great value on appearances, idealizing thinness as a beauty standard and primary indicator of health. The “Freshman 15” (the idea that students will gain 15 pounds during their first year of college) is a widely held belief that may encourage students to take dieting and exercise to unhealthy extremes; however, a recent study found that freshman participants only gained 2.5 to 3.5 pounds on average during the first year of college (Zagorsky, 2011). The problem seems to be increasing: a study at one college found that total eating disorders increased in both females (from 23% to 32%) and males (from 7.9% to 25%) during a 13-year period (White, Reynolds-Malear, & Cordero, 2011).

Recently, Jacobi, Fittig, Bryson, Wilfley, Kraemer, and Taylor (2011) reported that 11.2% of college-age women who endorsed high weight concerns developed an eating disorder over a three-year follow-up period, independently replicating previous work regarding risk of eating disorder onset in this high-risk group. According to the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA; 2013), eating disorders may begin with preoccupations about food and weight, but they are often about much deeper issues and emotions, often arising from a combination of long–standing behavioral, biological, emotional, psychological, interpersonal, and social factors.

In general, students coming to college tend to be more overwhelmed than they have been in previous years. In a national survey of counseling center directors, 70% reported a recent increase in the number of students with severe psychological problems in the last year alone, and 95.6% report that this is a growing concern for counseling centers (Mistler, Reetz, Krylowicz, & Barr, 2012); 78% report that it is impacting administration, and 69% report that it is even impacting university faculty (Gallagher, 2004). Many of the centers that participated in this survey received evaluation information from the clients; 67% of the students believed that counseling services helped their academic performance (Mistler et al., 2012), and 54.6% of students reported that counseling helped them to remain in school (Gallagher, 2004). Good mental health services help institutions retain students (Bishop, 2010; Wilson, Mason, & Ewing, 1997). However, students are not always aware of the resources available on campuses or may be reluctant to use them due to the stigma attached with receiving counseling. Additionally, it is common for people to deny the existence or seriousness of a problem, which hinders help-seeking (NEDA, 2013). It is therefore important to provide outreach, prevention, and educational campaigns (Kitzrow, 2003). According to NEDA, education and prevention programming takes place annually during National Eating Disorders Awareness Week on 65.6% of campuses, and nearly half (46.9%) reported having programs/workshops about eating disorders and body image issues at least once per semester.

Current Study

One of the outreach programs sponsored at Student Counseling Services is the Operation Beautiful campaign. This yearly campaign is conducted with the goal of decreasing body image issues that are typically prevalent, especially among college campuses. Ways in which the program works towards this goal is by encouraging students to reduce or eliminate negative self-talk and “fat-talk” and by promoting acceptance and appreciation of diversity in body shapes and sizes. The Operation Beautiful post-it note campaign is perhaps one of the most visible prevention programs.

Method

Participants

A total of 169 students completed the online survey. The sample was primarily female (89.4%). Respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 45 years [Mean (M) = 21.45, Standard deviation (SD) = 5.25] with the most common age being 21. The most represented races were European American/Caucasian (72.4%), African American (10%), and Asian/Pacific Islander (4.7%).

Materials and Procedure

A list of the messages on the post-it notes can be found in the Appendix. Student Counseling Services, in collaboration with the Student Wellness Ambassador Team (housed in Health Promotion and Wellness), worked to post anonymous post-it notes with positive messages in various campus buildings. Twenty-five buildings were targeted, and 15 to 20 notes were placed in each building. The notes remained posted for approximately one week. Afterwards, students were invited to take an online survey that included questions about body image issues and responses to the post-it notes. The following data are student responses to the campaign.

Results

A majority of respondents (71.8%) reported noticing the Operation Beautiful post-it notes on campus. The most common places students reported seeing notes were in academic buildings (47.6%) and in the Bone Student Center (31.2%). Of the students who saw the notes, 63.5% were able to recall some of the messages. The messages students remembered the most were “You are beautiful!” (34.7%), “Be beautiful, Be you!” (26.5%), and “Don’t worry. You look great!” (20%).

Change in Negative Self-Talk

Students were asked if they decreased their own negative self-talk after seeing the notes. In examining which students reported decreasing their own negative self-talk, there was a significant main effect of finding the Operation Beautiful campaign worthwhile, F(3, 166) = 4.46, p = .005, partial η2 = .08. That is, the more worthwhile the students felt the campaign was, the more likely they were to decrease their own negative self-talk (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Furthermore, there was a significant effect of noticing a decrease in “fat talk” among other students on the extent to which students believed the campaign was worthwhile, F(2, 167) = 3.52, p = .032, partial η2 = .04. In other words, students who noticed a change (increase or decrease) in “fat talk” among others found the campaign more worthwhile (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics). This suggests that any conversation about “fat talk,” regardless of the tone, increases feelings of worth about the Operation Beautiful campaign.

Table 1. Differences in Negative Self-Talk Based on Perceptions of Operation Beautiful as a Worthwhile Campaign

| Responses to “…Operation Beautiful is a worthwhile campaign”. | M | SD | n |

| Disagree | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2 |

| Neutral | 2.1 | 0.3 | 17 |

| Agree | 2.2 | 0.4 | 73 |

| Strongly Agree | 2.5 | 0.5 | 78 |

Table 2. Differences in Beliefs that Operation Beautiful is a Worthwhile Campaign Based on Noticing Changes in Fat Talk Among Others

| Responses to “Have you noticed a change in fat talk among other students?” | M | SD | n |

| Noticed Increase | 4.6 | 0.9 | 9 |

| Notice No Change | 4.3 | 0.7 | 129 |

| Noticed Decrease | 4.6 | 0.6 | 32 |

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine whether participant reports of decreasing negative self-talk, intention to decrease negative talk, and noticing decreases in “fat talk” among others were significantly different as a function of biological sex. The analysis revealed that there was a significant main effect of sex, Wilks’ Λ = .91, F(3, 165) = 5.32, p = .002, partial η2 = .09. Biological sex explained the largest amount of variance in noticing decreases in “fat talk” among others (partial η2 = .04), followed by intention to decrease negative self-talk (partial η2 = .03), and reports of actual decrease in negative self-talk (partial η2 = .01). Women reported higher intentions of decreasing negative self-talk, but men reported noticing decreases in “fat talk” in others more, as well as more actual decreases in negative self-talk (descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3).

Table 3. Differences in Negative Talk (Self and Others) as a Function of Biological Sex

| Item | Sex | M | SD | n |

| I am more likely to try to decrease negative talk about my body because of OB. | Male | 3.2 | 1.0 | 17 |

| Female | 3.7 | 0.8 | 152 | |

| Have you noticed a decrease in fat talk among other students? | Male | 2.4 | 0.5 | 17 |

| Female | 2.1 | 0.5 | 152 | |

| After reading the OB notes, have you decreased your own negative self-talk? | Male | 2.5 | 0.5 | 17 |

| Female | 2.3 | 0.5 | 152 |

Students were also asked about whether or not they engage in activities to decrease negative self-talk. Forty students gave examples of activities in which they engage, such as encouraging friends to not engage in “fat talk” (40%, e.g., “I’ve told my friends to stop it and that they are pretty just the way they are.”), using different words to describe themselves (20%, e.g., “Instead of saying I have fat thighs, I tell myself that I have strong ones because of how much I can squat. Instead of thinking I have a larger body frame, I tell myself I can pull off clothes that wouldn’t fit others so well.”), and being aware or conscious of their attitudes about their body (7.5%, e.g., “I consciously make myself aware of when it’s happening and try to stop it coming from myself.”).

Seeing and Believing the Post-it Notes

In examining how the Operation Beautiful post-it notes impacted participants, we found that 51.8% of students reported believing the messages sometimes, 30% reported believing the messages often, and 10% reported believing the messages always. There were no significant differences between men and women in reports of believing the messages, t(18.09) = .75, p = .47.

A MANOVA revealed that believing the messages on the notes had a significant omnibus effect on reports of decreasing negative self-talk, belief that the campaign is worthwhile, and reports of attempts to implement activities to decrease “fat talk,” Wilks’ Λ = .89, F(9, 399.28) = 2.18, p = .022, partial η2 = .04. Believing the notes explained the largest amount of variance in decreasing negative self-talk (partial η2 = .06), followed by belief that the campaign is worthwhile (partial η2 = .05) and reports of attempts to implement activities to decrease “fat talk” (partial η2 = .02). That is, students who believed messages more often were more likely to report decreasing in negative self-talk, higher levels of agreement that the campaign was worthwhile, and more attempts to implement activities that decrease “fat talk” (descriptive statistics are provided in Table 4).

Table 4. Differences in Positive Changes and Opinions as a Function of Believing Messages

| Item | Believe Message | M | SD | n |

| After reading the OB notes, have you decreased your own negative self-talk? | Never | 2.1 | 0.3 | 14 |

| Sometimes | 2.2 | 0.4 | 88 | |

| Often | 2.5 | 0.5 | 51 | |

| Always | 2.5 | 0.5 | 17 | |

| Please indicate the degree to which you agree with the following statement: “OB is a worthwhile campaign”. | Never | 4.4 | 0.9 | 14 |

| Sometimes | 4.2 | 0.7 | 88 | |

| Often | 4.4 | 0.6 | 51 | |

| Always | 4.8 | 0.4 | 17 | |

| Have you tried to implement any activities to decrease fat talk in yourself or others? | Never | 1.4 | 0.5 | 17 |

| Sometimes | 1.3 | 0.8 | 88 | |

| Often | 1.3 | 0.5 | 51 | |

| Always | 1.5 | .05 | 17 |

Students were also asked about initial thoughts/feelings when first reading the Operation Beautiful notes. After examining the qualitative data and categorizing the responses into ‘Positive,’ ‘Negative,’ and ‘Neutral’ reactions, it was found that 89% of students believed the messages to be positive, while 6% were negative and 5% were neutral with their reactions. Students that believed that the notes were positive wrote responses such as, “I smiled because a stranger wanted to help me (and everyone) have a great day and try to love themselves. I was glad that people were spreading positive.” An example of a negative response was, “Part of me wanted to think that it is sad that we have to remind ourselves we are in control of our image and positivity, and the other part of me felt sad because some people really do struggle keeping their images up and leading a healthy lifestyle.” Finally, a neutral reaction was, “I was a little confused as to what the poster was, but it was cool.”

Body Image Issues (Past and Present)

In examining which students report struggling with their body image, there was a marginally significant difference between men and women, t(167) = -1.80, p = .074. That is, women reported greater levels of current struggle with body image than men. We suspect that a sample with greater numbers of men would produce larger differences. To examine these differences in a different light, we conducted a MANOVA to determine the extent to which current body image struggles, frequency of body image struggles, and past body image struggles would differ as a function of biological sex. The analysis revealed that there was a significant main effect of sex, Wilks’ Λ = .90, F(6, 330) = 3.05, p = .006, partial η2 = .05. Biological sex explained the largest amount of variance in frequency of body image struggles (partial η2 = .25), followed by past body image struggles (partial η2 = .19) and current body image struggles (partial η2 = .05). Women reported higher levels of current struggle, greater frequency of struggle, and greater degrees of past struggle (descriptive statistics are provided in Table 5).

Table 5. Differences in Struggles in Body Image as a Function of Biological Sex

| Item | Sex | M | SD | n |

| To what degree do you currently struggle with your body image? | Male | 2.1 | 1.0 | 17 |

| Female | 2.5 | 0.9 | 152 | |

| How often do you struggle with your body image? | Male | 2.8 | 1.3 | 17 |

| Female | 3.3 | 1.1 | 152 | |

| To what degree have you struggled with your body image in the past? | Male | 2.5 | 1.1 | 17 |

| Female | 2.8 | 1.0 | 152 |

Note. Scores on the first and third items ranged from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Scores on the second item ranged from 1 (I do not struggle) to 5 (always).

Students were also asked to share qualitative information about their current and past struggles with body image. In regards to current struggle, there were 97 varying responses, including believing they were overweight (e.g., “I feel like my face is fat and it makes me self-conscious”), comparing themselves to others (e.g., “I feel that I constantly compare myself to my thinner friends. I feel that people are open to be my friends regardless of my weight but then other times I feel like they judge me or don’t give me a chance.”), and pressures from the media (e.g., “Today it seems impossible with the media to feel like you have the perfect body and to be comfortable being you. There always seems to be some way that you can be ‘perfecting’ your body.”). Other students who reported not having body image struggles provided responses such as, “I think we all have our days where we are unhappy with ourselves (inside and outside), but at the end of the day, I know who I am as an individual and I am confident and great with that person.”

In regards to past struggle, 78 students provided varying responses, including struggling with eating disorders (e.g., “I had symptoms of anorexia for awhile. I was almost 20 lbs underweight.”), bullying (e.g., “I have always been made fun of for my weight, and coming to college has almost been worse.”), or past issues that are the same as their current ones.

ISU and Body Image/Eating Disorders

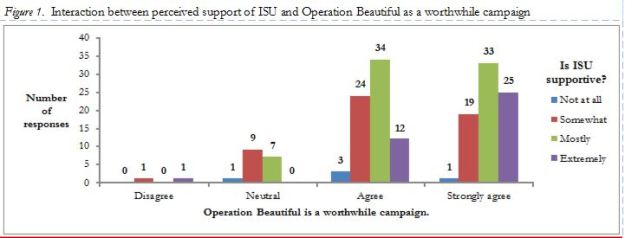

In examining differences in perceptions about how supportive ISU is of diversity among body types, shapes, and sizes, there were no significant differences between men and women, t(167) = -.83, p = .41. However, there was a significant difference in perceptions about ISU support based on the degree to which students believed the messages on the post-it notes, F(3, 166) = 2.85, p = .039, partial η2 = .05. Students who believed the messages more often felt that ISU was more supportive of body diversity (descriptive statistics are provided in Table 6). Additionally, participants who believed Operation Beautiful is a worthwhile campaign were more likely to report that ISU was more supportive of diversity in body types, shapes, and sizes, F(166) = 4.51, p = .005, partial η2 = .08. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 6. Differences in Beliefs About ISU’s Support Based on Believing Messages

| Do you believe the message you saw? | M | SD | n |

| Never | 2.9 | 1.0 | 14 |

| Sometimes | 2.7 | 0.8 | 88 |

| Often | 3.0 | 0.7 | 51 |

| Always | 3.2 | 0.9 | 17 |

Students were asked to share why they felt ISU’s campus was or was not supportive of diversity among body types, shapes, and sizes. A number of responses were provided, including highlighting the programs and campaigns provided on campus (e.g., “I feel like ISU does a good job promoting and encouraging diversity because it offers a wide assortment of activities students of different cultures or with different interests can become engaged in. I have been actively involved with alternative breaks and diversity is a huge part of what the trips seek to promote and open the eyes of students to see.”), seeing a diversity of body types across students, and believing the many flyers and ads posted around campus supporting body image.

For students who did not believe that ISU’s campus is supportive, most replied that the University does not do a good job with adjusting classrooms for larger people (e.g., “Well, as a bigger woman, I wish the desks were bigger, I seriously do not fit into most of them and have to have a chair and table brought in.”) or they believe their peers are not supportive of one another. Many students (16%) also commented on the effects that media has on students, therefore not making diversity ISU’s issue but society’s as a whole (e.g., “It’s a world where you’re expected to be thin. It’s not ISU’s problem alone- it’s just a society thing. There are people that just make you feel terrible about yourself everywhere you go.”).

Finally, there were significant differences between men and women in reports of whether or not they would seek help from Student Counseling Services if they were to experience body image issues, t(167) = -2.80, p = .006. Women were significantly more likely to report that they would seek help from Student Counseling Services for body image issues.

Discussion

College students do appear to struggle with body image issues, and while women seem to struggle more, this problem is not exclusive to women. Additionally, a stigma remains for seeking help at Student Counseling Services. Outreach campaigns such as Operation Beautiful help reach around the stigma to reach students who might be struggling in silence. We found that students did notice the Operation Beautiful post-it notes on campus and that the notes did have an impact on “fat talk”/negative self-talk and also on perceptions of support received from the University. Based on survey responses, we do believe the Operation Beautiful campaign was worthwhile and hope to continue the it in future years. This project helps us see where the Operation Beautiful campaign is strong and what issues might exist that we are currently not addressing within the campaign. Results of previous campaigns have suggested also targeting men who might be struggling with body issues. These results seem to corroborate this as men did report struggling with body image and were far less likely to report that they would seek help from Student Counseling Services for body image issues. A limitation of our findings is the small number of men in our sample. In the future, we hope to target more men for survey responses.

References

Bishop, J. B. (2010). The counseling center: An undervalued resource in recruitment, retention, and risk management. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 24(4), 248-260.

Gallagher, R. P. (2004). National survey of counseling center directors. Alexandria, VA: International Association of Counseling Services.

Jacobi, C., Fitting, E., Bryson, S. W., Wilfley, D., Kraemer, H. C., & Taylor, C. B. (2011). Who is really at risk? Identifying risk factors for subthreshold and full syndrome eating disorders in a high-risk sample. Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1939-1949.

Kitzrow, M. A. (2003). The mental health needs of today’s college students: Challenges and recommendations. NASPA Journal, 41(1), 165-179.

Mistler, M. J., Reetz, R. D., Krylowicz, B., & Barr, V. (2012). The association for university and college counseling directors annual survey. Retrieved from http://www.aucccd.org/support/aucccd_directors_survey_monograph_2012_public.pdf

National Eating Disorders Association. (2013). Eating disorders on the college campus: A national survey of programs and resources. Retrieved from http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/CollegiateSurveyProject

White, S., Reynolds-Malear, J. B., & Cordero, E. (2011). Disordered eating and the use of unhealthy weight control methods in college students: 1995, 2002, and 2008. Eating Disorders, 19(4), 323-334.

Wilson, S., Mason, T., & Ewing, M. (1997). Evaluating the impact of receiving university-based counseling services on student retention. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44(3), 316-320.

Zagorsky, J. L., & Smith, P. K. (2011). The freshman 15: A critical time for obesity intervention or media myth? Social Science Quarterly, 92(5), 1389-1407.

Appendix

- You are fantastic!

- Just be yourself!

- Be beautiful, Be You!

- You are beautiful!

- Start a revolution, stop hating your body!

- Change the way you see, not the way you look!

- You are perfect just the way you are!

- You are a beautiful person in your own unique way!

- You are magnificent!

- Do you want to meet the love of your life? Look in the mirror!

- You are extraordinary!

- Be you and you will never fail!

- You are strong!

- The key to success is to not set any limits. You can do it! Believe in yourself!

- Don’t follow someone else’s shadow…. its best to just make your own!

- Don’t Worry. You Look Great!

- You are a beautiful soul

- You are enough… just the way you are!

- I’m not perfect but that’s okay!

- What if I stopped comparing myself to others?

- Believe me. You are beautiful. Own it!

- No matter your age, your size, or your shape – you are beautiful!