See the statement at the end of this post about using earnings data in higher education.

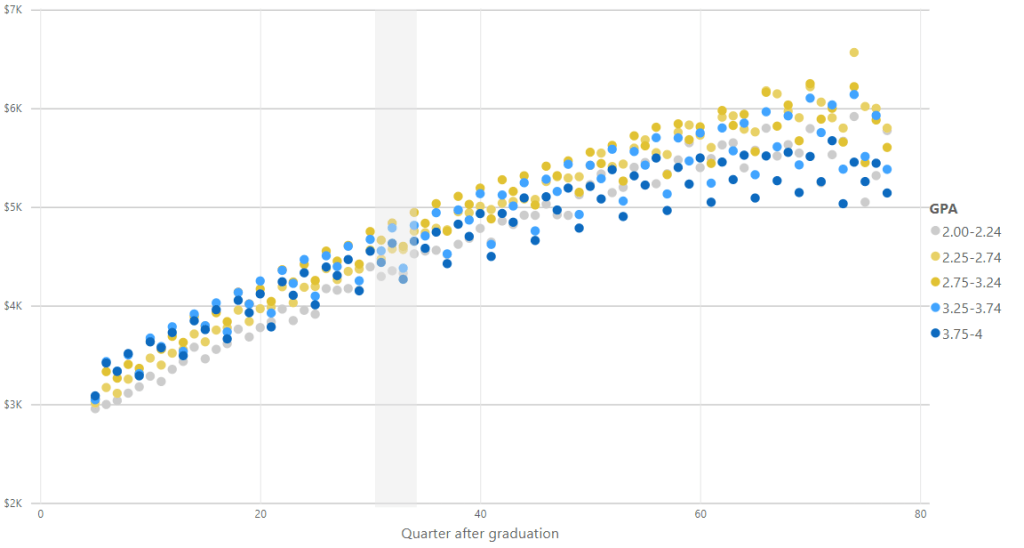

High GPA ISU graduates – the blue dots – start their career with higher earnings. The C and B graduates – the yellow dots – overtake their higher GPA colleagues in earnings around year seven (the vertical grey bar).

So, what’s going on?

Lower and mediocre GPAs don’t cause higher incomes. Other factors are likely at play. I have three hunches based on research and feedback I have received from faculty and colleagues.

1. C and B students invest more time in non-academic and academic activities outside of the classroom, like student-faculty research or senior culminating experiences.

Here, students learn how to collaborate, apply learning in practical settings, and integrate learning across disciplines. The idea is that employers look for these skills in the long-run. A-students invest more time in academic preparation, focus on a specific discipline, and spend less time in social, collaborative and integrative activities. In other words, they replicate career academics’ behaviors. As one myself, I say that with no judgment or criticism. I like working in an environment where every conversation with an academic expert is like a mini Ted Talk on subjects ranging from the physics of space travel to the economics of agriculture.

Collaboration, belonging and interactions are positively associated with student success at ISU and probably other institutions. Adam Grant writes:

Academic grades rarely assess qualities like creativity, leadership and teamwork skills, or social, emotional and political intelligence. Yes, straight-A students master cramming information and regurgitating it on exams. But career success is rarely about finding the right solution to a problem — it’s more about finding the right problem to solve.

Maybe B and C-students need more time to shine? Maybe they get more Cs because they avoid conforming academic behaviors that work those interested in academic careers, but not everyone else outside of academia?

In the 1998 film Rushmore, student Max Fisher is viewed as a “sharp little guy” by the wealthy entrepreneur Mr. Herman Bluth. The headmaster, Dr. Nelson Guggenheim, thinks Max is “one of the worst students we’ve got.”

This is symbolic of the gap between what academics assume and what everyone else assumes constitutes student success. Call it the Rushmore effect.

2. Employers use grades to screen new employees

Other than a degree, resume and maybe a transcript, most employers have little direct knowledge about what skills graduates possess. So they rely on the most universally understood, clear, and available indicator: GPA. But only in the first few years. A’s and good grades don’t really matter the longer one is in the workforce.

3. Some A students may be missing out

The idea here is that many A students are strategic learners. Strategic learners are dialed in on the grade and are more likely to conform to an academic system instead of challenging it. So, they avoid risk-taking behaviors. They may strategically seek out courses where the probability of getting an A is higher.

Or avoid non-academic activities. Adam Grant writes:

Straight-A students also miss out socially. More time studying in the library means less time to start lifelong friendships, join new clubs or volunteer.

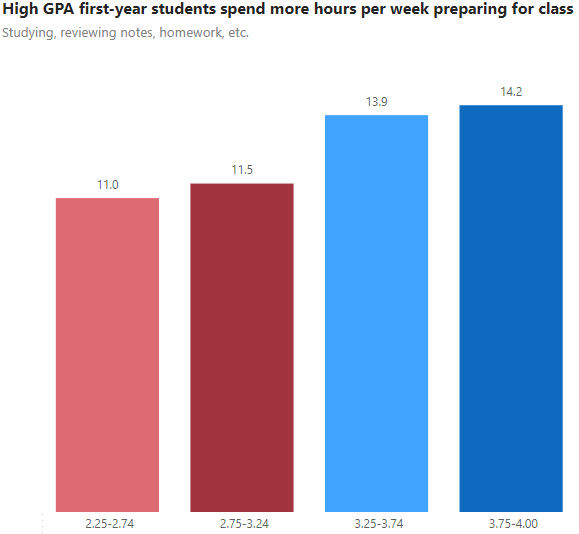

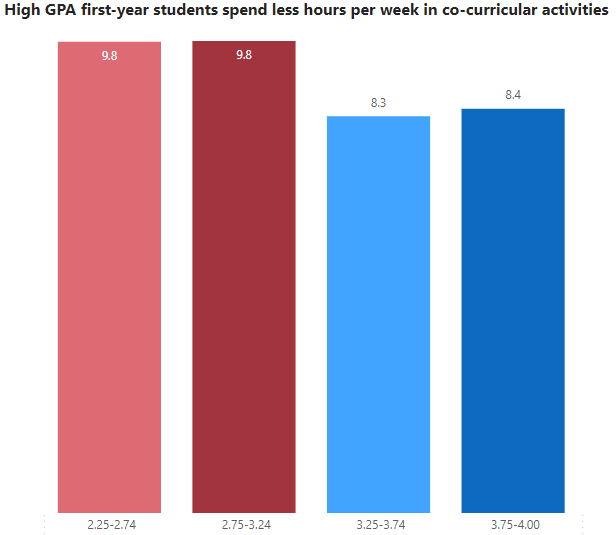

ISU survey results show that high GPA students spend more time on academic endeavors. Lower-GPA students spend more time in co-curricular activities. Maybe there’s something to this idea.

Is a high GPA a bad thing?

I don’t think so. Lots of A-students are doing it right. I teach an Honors section and know many of them. They work hard, engage in deep learning and have a growth mindset. I am confident this group of A-students will be fine.

Implications for Practice

Successful students feel like they belong, engage in positive and frequent interactions with others, know how to collaborate, and are engaged in academic activities outside of the classroom

The extent to which a university can emphasize these factors – and teach students how to do them – positively impacts only retention. These skills could also enhance the economic and non-economic benefits of attending college.

Communicate to low and moderate GPA students they will be fine…but don’t be a slacker

I have a hunch that GPA is as much of an indicator of academic progress as it is a signaling device to students whether they belong in college. Students with lower GPAs may view GPA as a signal they don’t belong in college or can’t accomplish their goals.

Communicating success stories from professionals and other students and encouraging engagement with learning support services – as opposed to punitive and bureaucratic solutions – could improve GPA and retention.

A high undergraduate GPA is sometimes a necessity for students to meet their goals

Some fields require high GPAs for admission to graduate school. My daughter is majoring in speech pathology. She will need a really high GPA for admission to a graduate program. I might have a different message for my son, who is thinking about information technology.

Higher GPAs in fields like art history – my undergraduate major – are not associated with long-term earnings. If asked by a student, I would be honest and admit Cs do get degrees. But my main message would be:

ISU provides a highly engaging undergraduate experience, more so than many other universities. You get out of college what you put into it. So do what you need to do and make the most of it while you’re here.

Earnings are not the only outcomes of college

This analysis does not assume the goal of a university is to prepare students for careers. Nor does it assume earnings are the only or best outcome of higher education. Higher education is associated with all kinds of non-economic benefits to individuals and society. These include health and wellness, the environment, human rights, and democratic engagement, to name a few. Walter McMahon has covered these benefits extensively.

Most studies show a positive correlation between GPA and earnings. However, nearly all of these studies only look at the first year or two. The impact of college is lifelong. The first few years are messy. I call it “living in my high school bedroom until I figure things out” phenomenon. Reporting earnings for only the first few years paints an incomplete picture of the lifetime earnings of college graduates. And misses the high returns on public investments in higher education.

Still, for many students, a college degree represents an escape from poverty and ending a cycle of intergenerational inequality. It represents a job with health care, retirement benefits and meaning. It doesn’t mean everything, but it counts for something.